Introduction

Sea turtles are adapted to their marine environment, and they possess unique anatomic and physiologic features that influence their restraint and handling. The wing-like front flippers are used for propulsion, while the oar-shaped hind limbs usually function as rudders for steering. The front flippers are very strong and can cause serious injury to the turtle and/or handler if not restrained properly. Although healthy sea turtles will slap with their flippers and may try to bite, manual restraint can be used for most non-invasive procedures.

Handling small sea turtles

Grasp small sea turtles along the anterior and lateral margins of the shell while the flippers are restrained at the shoulder with both hands (Fig 1). The turtle is pulled close to the handler’s body when carried.

Figure 1. Proper restraint of a small sea turtle. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

It is important to control the flippers while still allowing some movement. Small green turtles (Chelonia mydas) are especially prone to proximal humeral fractures during handling (Fig 2). Such injuries are more likely to occur when the forelimbs are overly restricted or when the animal is restrained by the flippers alone.

Figure 2. Small green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) are prone to proximal humeral fractures if improperly restrained. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Handling large sea turtles

It is best to have two or more individuals restrain large sea turtles. Firmly grasp the turtle by the carapace, just caudal to the head, with one hand and along the posterior carapace dorsal to the hind flippers with the other hand (Fig 3, Fig 4).

Figure 3. Firmly grasp larger sea turtles just caudal to the head with one hand and along the posterior carapace with the other hand. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 4. To restrain and move large sea turtles, it is best to have two or more individuals carry the turtle. One hand firmly grasps the posterior carapace dorsal to the hind flippers (arrow), while the other hand grasps the carapace just behind the head. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Handling aids

Regardless of patient size, covering the eyes may help calm the turtle (Fig 5).

Figure 5. A loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) undergoing an MRI with the use of toweling to cover the eyes. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

At the Georgia Sea Turtle Center (GSTC), several different sizes of restraint devices called “Turtle Tamers” aid in weighing and examining sea turtles (Fig 6, Fig 7). Inner tubes and tires can also be used to position turtles and provide padding (Fig 8).

Figure 6. Makeshift restraint devices, called “Turtle Tamers” (left) at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center, are used to aid in weighing and examining sea turtles (right). Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 7. Close-up of a “Turtle Tamer” used at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center used to aid in examination of a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii) with a carapacial injury and attached vacuum assisted wound care apparatus. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 8. Inner tubes and tires can also be used to position turtles and provide padding. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Specially designed slings may be needed to lift heavy adults (Fig 9, Fig 10). The GSTC has custom-made slings created by Ortega’s Canvas & Sail Repair (Carlsbad, California).

Figure 9. Custom made slings can be used to lift heavy, adult sea turtles. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 10. A sling–and lots of “elbow grease”–is used to carry a heavy adult sea turtle. At least one person should monitor the turtle’s head so that it does not drag on the ground and to prevent the turtle from biting the bearers. Photo credit: Georgia Sea Turtle Center. Click image to enlarge.

Once in the hospital setting, low, wheeled, padded transport, or even wheelbarrows, can be invaluable for moving large turtles (Fig 11).

Figure 11. Large turtles can be moved around the facility on low, padded trolleys. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Caution

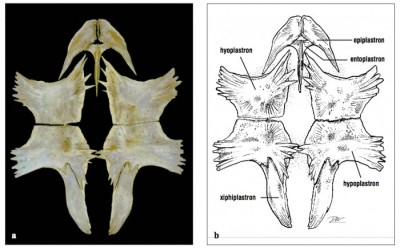

Take care when handling debilitated turtles. Several cases of pericardial and cardiac tears by the sharp plastron bones have been documented due to the mobility of the sharp entoplastron and hyoplastron bones. These bones are particularly mobile in debilitated loggerheads (Fig 12, Fig 13).

Figure 12. Debilitated loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) are at risk for pericardial and cardiac tears from the plastron. Photo credit: Dr. Terry Norton. Click image to enlarge.

Figure 13. In sea turtles, the plastron is composed of four paired bones and one unpaired bone, the entoplastron. These bones are separate in hatchlings, but become fused in adults. The connective tissue holding the bones together weakens in debilitated turtles. Photo credit: Dr. Jeanette Wyneken. Click image to enlarge.

**Login to view references**

References

References

Norton TM. Sea turtle rehabilitation. In: Miller RE, Fowler M (eds). Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Therapy Volume 7. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier Saunders;2012: 239, 242.

Wyneken J. The Anatomy of Sea Turtles. U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum. NMFS-SEFSC-470, 1-172, 2001.

Wyneken J, Mader DR, Weber ES, Merigo C. Medical care of sea turtles. In: Mader DR (ed): Reptile Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA, WB Saunders, 2006:972-1007.

Norton T, Wyneken J. Sea turtle restraint. January 27, 2015. LafeberVet Web site. Available at https://lafeber.com/vet/sea-turtle-restraint/