Mediterranean Tortoises (Genus Testudo)

Bronze statue of ‘Testudo’, the University of Maryland mascot. Photo credit: Mark Zimmerman via Flickr Creative Commons

Natural history

Mediterranean tortoises are native to arid regions in Mediterranean Europe, Africa, and parts of the Middle East. Most Testudo species are primarily herbivorous and they practice brumation (or hibernation) in the wild.

Taxonomy

Class: Reptilia

Order: Chelonia/Testudines

Family: Testudinidae

Genus: Testudo

Testudo marginata (Marginated tortoise)

T. weissingeri, originally classified as a dwarf population or subspecies of T. marginata

T. horsfieldii (Russian tortoise)

T. graeca (Greek spur-thighed tortoise) not to be confused with the spurred tortoise, Geochelone sulcata

T. ibera (Greek spur-thighed tortoise)

T. hermanni (Hermann’s tortoise)

T. kleinmanni (Egyptian tortoise)

Physical description

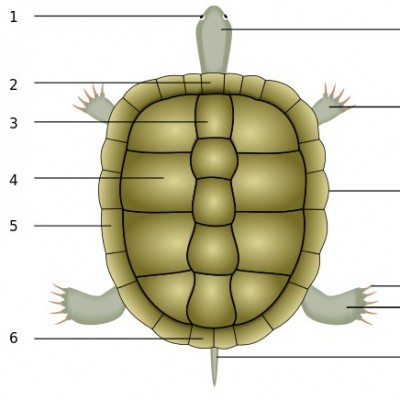

The members of genus Testudo are medium-sized tortoises. Various features of the shell, such as the supracaudal scute (#6 left), tail, and thighs can be used to distinguish species (see table below). Photo credit: Titimaster via Wikimedia Commons Click image to enlarge

The members of genus Testudo are medium-sized tortoises. Various features of the shell, such as the supracaudal scute (#6 left), tail, and thighs can be used to distinguish species (see table below). Photo credit: Titimaster via Wikimedia Commons Click image to enlarge

| Some distinguishing characteristics of Mediterranean tortoise species commonly seen in the pet trade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian tortoise | Russian tortoise | Hermann’s tortoise | Greek tortoise | Marginated tortoise | |

| Straight carapace length (cm) | 10-12 | 12-20 | 13-20 | 18-21 Testudo (graeca) ibera 13-16 T. g. graeca |

25-40 |

| Shell shape | High domed | Broad, rounded, dorsoventrally flattened, sometimes with a dorsal ridge | Arched, rounded | Oblong, domed | |

| Carapace color | Usually pale, dull yellow but can range from near gray to ivory to rich gold | Green-brown to black fading to yellow between scutes | Yellow with black | Brown-yellow with black | Pale yellow on black |

| Carapacial scutes | Supracaudal scute is flared | Usually possess a divided supracaudal scutes | Undivided supracaudal scute | Supracaudal and posterior marginal scutes are prominently flared | |

| Plastron | Pale yellow with two dark, clearly marked triangular notches or chevrons | ||||

| Foreleg | Five toes on forefeet

Three longitudinal rows of large scales on anterior surface of forelimb |

Four toes on forefeet | Five toes on forefeet | Five toes on forefeet | Five toes on forefeet

Four or five longitudinal rows of large scales on anterior surface of forelimb |

| Thigh | Tubercles or enlarged scales on thighs | Enlarged tubercles on medial thighs | USUALLY lack spurs on thighs | ||

| Tail | Horny claw or spur on end of tail | Horny claw or spur on end of tail | USUALLY lack spur on tail | ||

| Head | Most Testudo h. hermanni have a characteristic yellow fleck on the cheek | ||||

Although female Mediterranean tortoises display slight mobility of the caudal plastron, sex determination is usually based on:

- Tail length: Males tend to have longer tails.

- Plastron conformation: Males tend to have a prominent concavity to the plastron, which facilitates mounting females for mating.

- Relative position of the vent or cloacal opening with respect to the caudal aspect of the carapace: The male vent is located further away from the body and closer to the tip of the tail.

- Body size: Females are also usually larger than males. Females also tend to be broader and heavier.

Diet

Mediterranean tortoises are primarily herbivorous and the bulk of the diet should be rich in vegetable fiber as well as calcium and carotenoids (vitamin A precursors). Although vitamin D3 is provided by exposure to sunlight or UVB-emitting bulbs, Mediterranean tortoises can also utilize vitamin D2 from plants.

These hardy tortoises often live under harsh conditions in the wild where food is scarce. They are opportunistic feeders, consuming a wide range of nutrient intakes out of necessity.

- Tortoises should be allowed to graze on grasses and weeds whenever possible, with care taken to avoid plant matter exposed to herbicides or pesticides.

- Wild tortoise diets typically contain a calcium:phosphorus ratio of up to or at times more than 4:1. Excess calcium can cause medical problems and this ratio should approximate 2:1 in captivity.

- Ensure the diet contains foods with high levels of carotenoids, especially beta-carotene, found in dark, leafy green vegetables as well as orange and yellow vegetables such as sweet potato, carrots, and squash.

- The diet should contain optimal, but not excessive, essential nutrients such as fatty acids, amino acids, fat- and water-soluble vitamins, and macro- and micro-minerals, including phosphorus.

- Offer food blended together in mixtures to reduce selective feeding.

Water should be available at all times. Provide a dietary calcium supplement, such as human-grade calcium carbonate, calcium citrate, or calcium phosphate, mixed into the vegetarian diet. Any commercial dried or pelleted tortoise diet offered should be fibrous and the primary ingredient should be grass hay. Place food on tiles or in dishes to prevent accidental ingestion of substrate along with food items. Also place food at the brighter end of the enclosure as illumination can stimulate appetite. Do not place food directly underneath heat sources to prevent drying.

Housing

Temperature

Optimal temperature ranges are species specific, with those from desert regions thriving in warmer, drier habitats. Generally, the daytime temperature gradient for Testudo species should range from 26ºC-30ºC (78.8ºF-86ºF) with a basking spot that reaches 30ºC-33ºC (85ºF-90ºF). The nighttime temperature should fall no lower than 18ºC (64.4ºF).

The use of a thermostat is recommended for every enclosed tortoise habitat.

Humidity

Provide species-specific environmental relative humidity levels. Juvenile tortoises may require higher environmental humidity levels to prevent shell pyramiding. Desert species such as the Golden Greek tortoise and Kleinmann’s tortoise require drier environs; constant high humidity appears to predispose these species to upper respiratory infections.

Also provide a humidity box, which simulates a humid underground burrow. Use a dark, plastic container with a cut entrance and moistened paper towels or sphagnum moss.

Water

Tortoises must be given regular access to fresh, clean water for drinking and bathing. Regularly soak tortoises in warm, shallow water for 10-20 minutes at intervals appropriate for the species. Soak most adults about once weekly, and hatchlings daily. Soaking encourages drinking, urination, and defecation. A bathing tortoise should NEVER be left unattended as it can upend and drown, even in shallow water.

Cage size and design

Excluding juveniles, measuring up to 10 cm (4 in) in length, provide outdoor enclosures whenever environmental constraints permit.

- Provide tortoises with the largest habitat that space allows as free-ranging tortoises utilize ranges measured by hectares or square miles. Pens should measure at least 12 square feet (1.1 sq m) and preferably 24 square feet (2.2 sq m) for larger species.

- Avoid clear walls, as tortoises will attempt to move through or over any barrier that allows them to see the world beyond.

- Outdoor enclosures should be well-drained and encourage foraging on grasses and broadleaf plants.

- Pens should be located in a sunny area with shaded spots and shelter for protection and thermoregulation.

- Pens should also afford protection from predators such as dogs, foxes, rats, and birds such as secure, screened covers.

- Outdoor enclosures must also prevent escape as these species can not only dig and burrow, but they are also adept at climbing.

- If multiple animals are housed in an enclosure, provide sightline breaks or opportunities for visual security. Monitor groups closely for signs of stress or fighting, as males may pester females until the latter lose weight or are upended, and certain individuals will also fight with other males.

An indoor cage or pen should also be set-up for housing the tortoise during cooler temperatures or when outdoor climatic conditions are not suitable.

- An open-topped pen that can be disinfected is recommended.

- Glass tanks and vivaria are generally unsuitable because good ventilation is essential.

- Enclosure should provide an appropriate temperature gradient and may require both an overhead and under-substrate heat source so that tortoises can thermoregulate naturally. Care must be taken to prevent fires when using heat sources with potential combustibles like bedding and hay.

Provide several, suitable hiding spots in both indoor and outdoor pens so that each tortoise has multiple choices for cover. Hiding places should be located at variable distances from the habitat’s principal heat source and should provide adequate cover from the sun or other light and heat sources.

Cage furniture/supplies

Exposure to natural sunlight is optimal for Testudo spp. It is unclear if indoor tortoises require full-spectrum lighting when adequate dietary vitamin D3 or D2 is provided. Nevertheless full-spectrum ultraviolet (UVB emitting) lighting improves activity and behaviors for those housed indoors and is recommended. In indoor settings, UVB spectrum lighting needs to be provided for 10-12 hours minimum. Maintain UVB lights within 30-46 cm (12-18 in) of the animal. Bulbs should be replaced regularly, probably every 6-12 months.

A shallow, sturdy pan, such as a ceramic plant saucer, is needed for soaking and drinking (see water above). Also provide cage furniture that stimulates activity and breaks up the line of sight along the pen wall.

Substrate

Select a friable, malleable substrate that allows the tortoise to right itself. Suitable substrates include alfalfa or grass hay pellets, large bark chips, hemp, newspaper, shredded paper, indoor/outdoor or reptile carpeting, and peat or soil mixtures (sterilized topsoil, coconut earth). There is no one perfect substrate so research pros and cons of each to find one best suited for a specific habitat. Due to risk of ingestion and intestinal blockage, avoid sand, cat litter, crushed corncob, or walnut shells. The depth of the substrate should enable burrowing.

Social structure

Chelonia in general are not social species, although they can be gregarious at certain times. Mixing incompatible species or individuals with prominent differences in size can result in larger animals monopolizing food, water and/or shelter. Amorous males may upend females or other males, which can be fatal.

All tortoises are best kept in small groups of one species and new animals should never be introduced without a lengthy period of quarantine (at least 3-6 months).

Overwintering

Proper overwintering will prevent the need for hibernation (see below) by providing a suitable environment so the tortoise can remain awake throughout the winter. Overwintered tortoises are supplemented with 12-14 hours of light during the day and heat from fall through spring. The optimal temperature range is 18-25ºC (64-77ºF) during the day, falling to 14-16ºC (57-61ºF) at night. There are anecdotal reports that suggest hibernation is necessary for successful breeding in captivity, but it may be unnecessary.

Hibernation/aestivation

Some Testudo species aestivate during very hot midsummers in their natural environments (e.g. Testudo kleinmanni), and they can also hibernate during the winter months. Healthy captive adults may be allowed to brumate at cooler temperatures for a few months. To prevent clinical problems, a pre-hibernation physical examination is strongly recommended. In northern latitudes, unmanaged, captive tortoises can potentially hibernate for up to 5 or 6 months, which can needlessly expose them to metabolic stress.Therefore the recommended maximum length of hibernation is approximately 3 months for a healthy, adult captive tortoise. Hibernation is carried out at approximately 5ºC (41ºF). Temperature should never be permitted to fall below 0ºC (32ºF).

Since there are numerous risks and potential for management errors, further reading is recommended before hibernating Mediterranean tortoises for the first time.

Lifespan

Tortoises are known for their longevity and with proper care Testudo species can live well into their 50s, possibly to 100 years.

Anatomy/ physiology

Dermatology

Chelonians possess a tough, horny beak instead of teeth.

The shell consists of bony plates covered with keratinized epidermal shields called “scutes”. The upper shell is called the “carapace” and the bottom shell is the “plastron”.

Respiratory

The respiratory anatomy and physiology of Testudo spp. are consistent with that seen in other chelonians:

- A relatively short trachea bifurcates into a left and right intrapulmonary bronchus at the level of the thoracic inlet.

- Complete tracheal rings

- The lungs are located just beneath the carapace, and the lungs are large and sac-like with many septae.

- The lungs have limited expansion capabilities due to the presence of the bony shell.

- Absence of a muscular diaphragm.

- The thoracic and pelvic girdles reside inside of the shell. Retraction and expulsion of the forelimbs from the shell is necessary for active inspiration and exhalation.

Urogenital

- Chelonians have a thin-walled, very distensible, bilobed bladder that serves as a water storage organ.

- A single, large, smooth copulatory phallus sits on the floor of the cloaca.

- The kidneys cannot concentrate urine because the nephrons lack a loop of Henle.

- Generally, Mediterranean tortoises lay one to three clutches per year, each containing one to five eggs. Incubation is generally accomplished at about 29-31ºC (84-88º F) and 70%-80% relative humidity for approximately 55-80 days.

Sexual dimorphism

Restraint

Most small to medium-sized tortoises are relatively easy to handle:

- Hold the shell midway between the front and rear legs.

- Most individuals will retract their heads into the carapace when handled. If possible, briefly restrain the forelimbs along the side to provide access to the head. Placing the thumb and middle finger behind the occipital condyles also prevents retraction of the head.

- If the tortoise retreats into its shell, sedation may be needed as too much force when trying to extend the legs and head can injure the animal. Sedation is often required to perform a physical examination in larger Testudo species.

- Hold the tortoise securely as the shell can chip or crack if the animal is dropped.

Cautions:

- While tortoises are usually not aggressive, these animals can use their strong, sharp beaks to bite quite firmly, often showing reluctance to let go once they have bitten.

- Personnel should prevent their fingers from becoming inadvertently pinned against the shell when a limb is suddenly withdrawn.

- Chelonians are considered an important source of Salmonella spp. infection in humans. Wear gloves when handling these species and always wear a fresh pair of gloves to handle each individual, unless tortoises are kept together as a group. After handling a tortoise or any part of its environment, wash hands thoroughly using soap and warm water.

Venipuncture

Brachial/ulnar venous plexus

Dorsal coccygeal venous sinus

Jugular vein (the right vessel tends to be larger)

Occipital sinus

Subcarapacial sinus (vein and plexus)

Preventive medicine

Regular physical examination

- Visits should emphasize client understanding of proper husbandry requirements, fastidious hygiene practices, and stringent biosecurity practices.

- Examine tortoises before and after brumation, ensuring that ill, debilitated, and/or underweight tortoises are not allowed to brumate. Ensure that inexperienced keepers are informed of the risks associated with hibernation.

Quarantine

Fecal parasite testing of new tortoises and then annually

Note: Do not use ivermectin in chelonians due to the danger of toxicity.

Zoonotic potential

Potential pathogens of chelonians with zoonotic potential include Salmonella spp., Campylobacter, and Zygomycoses.

Educate owners about the risks of owning tortoises and appropriate husbandry and sanitation procedures.

Important medical conditions

- Herpesviral infection: All Testudo species are potential carriers of herpesvirus genotypes TeHV1 and/or TeHV3.

Clinical disease associated with TeHV1 is more common in the spring. Although this genotype is associated with low morbidity and mortality in Russian tortoises (Testudo horsfieldi), which are often carriers, it is typically a fatal disease in other chelonian species as TeHV1 is frequently complicated by secondary bacterial infection.

Tortoise herpesvirus 3 (TeHV3) infection causes particularly severe disease and high morbidity and mortality in Russian tortoises, and outbreaks in tortoises generally often occur after introduction of T. horsfieldi.

- Upper respiratory tract disease (URTD) or rhinitis caused by Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila, Pasteurella testudinis, etc.

Note: A Testudo species with URTD is much more likely to have primary herpesviral infection. - Lower respiratory tract disease, pneumonia

- Endoparasites: nematodes, Ascarid worms

- Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism (metabolic bone disease)

- Pyramiding or “pyramid growth syndrome” abnormal development of the carapace in which the scutes are raised in the center (e.g., development of a pyramid-shaped osseous growth centrally within the horny plates), related to metabolic bone disease and/or inadequate environmental humidity;

- Hepatic lipidosis due to excessive feeding, lack of exercise, and/or lack of hibernation or natural fasting in temperate species that are not normally maintained year-round. Females that do not have the opportunity to breed also appear particularly at risk.

- Hypovitaminosis A

- Iatrogenic hypervitaminosis A

- Renal disease

- Urinary bladder stones

- Paraphimosis

- Cloacal prolapse; oviductal, urinary bladder, and/or colon prolapse

- Dysecdysis: incomplete or retained sheds involving toes, tail, or skin around the oral cavity, eyes, and eyelids

- Keratopathies and cataract formation during hibernation

Other reported conditions include cryptosporidiosis, ranavirus infections (iridoviral disease), and picornavirus infection.

Signs of ranavirus are very similar to herpesviral disease and iridoviral infection is usually fatal in wild and captive chelonians).

Picornaviruses (“virus X”) are regularly detected in Testudo species or subspecies, with the exception of Testudo horsfieldi, and “virus X” is often found together with other infectious agents (e.g., herpes viruses, Mycoplasma).

Quiz

Click here to access LafeberVet’s Testudo Tortoise Fast 5 Quiz.

**Login to view references**

References and further reading

References

American Association of Zoo Veterinarians Infectious Disease Committee Manual. 2013. Testudinid Herpesviruses. Website title. Available at http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.aazv.org/resource/resmgr/IDM/IDM_Herpesviruses_in_tortois.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2015.

Chitty J, Raftery A. Essentials of Tortoise Medicine and Surgery. Wiley-Blackwell. 2013.

de Vosjoli P. Tortoise husbandry 101. Exotic DVM 2003;4.6:27-30.

Eatwell K. Captive care of Mediterranean tortoises (Testudo sp). Irish Vet J 2009;62(2):125-129.

Franklin J. Horsfield’s (Russian) tortoise (Testudo horsfieldii). Exotic DVM 2007;9.4:30-31.

Gibbons PM, Klaphake E, Carpenter JW. Reptiles. In: Carpenter JW (ed). Exotic Animal Formulary, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2012: 156.

Hidalgo-Vila J, Díaz-Paniagua C, Ruiz X, et al. Salmonella species in free-living spur-thighed tortoises (Testudo graeca) in central western Morocco . Vet Rec 162(7):218-219, 2008.

Highfield AC. Basic care of Mediterranean tortoises. The Tortoise Trust. Available at http://www.tortoisetrust.org/articles/Basicmedcare.htm. Accessed June 8, 2014.

Highfield AC. The causes of “Pyramiding” deformity in tortoises: a summary of a lecture given to the Sociedad Herpetologica Velenciana Congreso Tortugas on October 30 2010. The Tortoise Trust. Available at http://www.tortoisetrust.org/articles/pyramiding.html. Accessed June 8, 2014.

Hnízdo J, Pantchev N, eds. Medical Care of Turtles and Tortoises: Diagnosis, Therapy, Husbandry, Prevention. Edition Chimaira. 2011.

Hunt CJG. Herpesvirus outbreak in a group of Mediterranean tortoises (Testudo spp). Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 2006;9:569-574.

Jepson L. Mediterranean Tortoises. Kingdom Books. City 2006.

Kuzman SL. The Turtles of Russia and Other Ex-Soviet Republics. Frankfurt am Main. 2002.

Lecis R, Paglietti B, Rubino S, et al. Detection and Characterization of Mycoplasma spp. and Salmonella spp. in Free-living European Tortoises (Testudo hermanni, Testudo graeca, and Testudo marginata). J Zoo Wildl Med 47(3):717-724, 2011.

Mader DR. Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2nd ed. Saunders. 2005.

Mader DR, Divers SJ. Current Therapy in Reptile Medicine and Surgery. Saunders. 2013.

Mayer J, Donnelly TM. Clinical Veterinary Advisor: Birds and Exotic Pets. Saunders. 2012.

McArthur S, Wilkinson R, Meyer J. Medicine and Surgery of Tortoises and Turtles. Blackwell Publishing. 2004.

O’Malley B. Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of Exotic Species. Edinburgh: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. Pp. 156-157.

Parham JF, Macey JR, Papenfuss TJ, Feldman CR, Türkozan O, Polymeni R, Boore J. The phylogeny of Mediterranean tortoises and their close relatives based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences from museum specimens. Mol Phylogenet Evol 2006;38:50-64.

Pasmans F, De Herdt P, Chasseur-Libotte ML, et al. Occurrence of Salmonella in tortoises in a rescue centre in Italy. Vet Rec 146(9):256-258, 2000.

Tabaka C, Senneke D. Egyptian tortoise – Testudo kleinmanni. World Chelonian Trust, Available at http://www.chelonia.org/Articles/tkleinmannicare.htm. Accessed on July 25, 2014.

The Tortoise Trust. Taking Care of Pet Tortoises. Available at http://www.tortoisetrust.org/Downloads/Taking_care_of_pet_tortoises_web.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2014.

Toombs L. Basic husbandry and common health problems associated with Mediterranean tortoises. Veterinary Nursing Journal 2013;28(12):400-404.

Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [Van Dijk PP, Iverson JB, Shaffer HB, Bour R, Rhodin AGJ]. 2012. Turtles of the world, 2012 update: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. In: Rhodin AGJ, Pritchard PCH, van Dijk PP, Saumure RA, Buhlmann KA, Iverson JB, Mittermeier RA (Eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 5, pp. 000.243-000.328, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v5.2012, www.iucn-tftsg.org/cbftt/.

Pollock C, Kanis C. Basic information sheet: Mediterranean tortoises. Mar 18, 2015. LafeberVet Web site. Available at https://lafeber.com/vet/basic-information-sheet-mediterranean-tortoises/