Grey Parrots’ Deductive Reasoning — Part I

Studies of deductive reasoning have allowed researchers to compare the intelligence of many nonhuman species with one another and with humans (see review in Völter & Call, 2017). The most common study involves what is technically called “inference by exclusion” or, in layman’s terms, “process of elimination.” Here a reward is hidden in one of two cups: A, B. One cup is shown to be empty, and the successful subject searches for the reward in the other cup: the assumed logic is “A or B; not A, therefore B”; which is also known as a “disjunctive syllogism.” It turns out, however, that a successful subject may be using something other than deductive reasoning to succeed — some logic that is actually much simpler — and that’s the subject of this posting.

The first problem is one of avoidance — the subject might just be avoiding the empty cup, or the cup that was most recently touched by the experimenter. Such a strategy has nothing to do with inference, which is what we are trying to test. One way around this is to give several trials in which two equally desirable different foods are shown to be hidden in the A and B cups (see Figure 1).

The first problem is one of avoidance — the subject might just be avoiding the empty cup, or the cup that was most recently touched by the experimenter. Such a strategy has nothing to do with inference, which is what we are trying to test. One way around this is to give several trials in which two equally desirable different foods are shown to be hidden in the A and B cups (see Figure 1).

Then the experimenter engages in two different actions: in one, the researcher places a screen between the cups and the subject, removes one of the foods (say from cup A) so that the subject doesn’t see the cup being emptied, removes the screen, and then eats that food while the subject watches; in the other, the experimenter simply eats a replica of one of the foods in front of the subject, with no removal or manipulation taking place. In both cases, the experimenter touches both cups and then presents them to the subject.

Good Choices

Good Choices

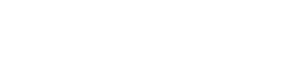

In the first case, the subject should infer that the food in cup A was eaten and choose cup B in order to get some kind of reward (see Figure 2). In the second case, the subject should choose at random, because there is no reason to expect that anything has been removed or that any reason exists to choose one cup over another if the treats are equally desired. Grey parrots succeeded very nicely (Pepperberg et al., 2013; see also Mikolasch et al., 2011).

These tests solve the problem of avoiding “empty” or the most recently touched cup, and suggest some level of inference, but do not address the problem of avoiding a cup from which a particular item has been removed. To deal with that possibility, we did the following experiment.

On some trials, we placed two treats, of differing value, under each cup in full sight of the birds…e.g., two hearts versus two pieces of chow (see Figure 3). Then we would, behind the screen, remove either one piece of chow or one piece of candy, and show them what we had removed. If they understood the task, in either case they should choose the candy side, as even one piece of candy is worth more than two pieces of chow — and they succeeded (Pepperberg et al., 2013).

On some trials, we placed two treats, of differing value, under each cup in full sight of the birds…e.g., two hearts versus two pieces of chow (see Figure 3). Then we would, behind the screen, remove either one piece of chow or one piece of candy, and show them what we had removed. If they understood the task, in either case they should choose the candy side, as even one piece of candy is worth more than two pieces of chow — and they succeeded (Pepperberg et al., 2013).

We also, of course, had to perform control trials for odor (showing them pairs of cups with food in only one side and making sure they would choose randomly), check for interobserver reliability by having multiple people score the birds’ behavior, and making sure that humans weren’t cuing the birds by some inadvertent movement. All the birds also did well on all these trials.

Although it would seem that these studies clearly showed that the birds were inferring the placement of the rewards by exclusion, it turns out that there are actually additional explanations that refute the “A or B; not A, therefore B” rationale. We’ve recently done several experiments to eliminate some of those possibilities, but that will be the subject for “Part II” in a few months!

Mikolasch, S., Kotrschal, K., & Schloegl, C. (2011). African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus) use inference by exclusion to find hidden food. Biology Letters, 7, 875–877. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0500

Pepperberg, I.M., Koepke, A., Livingston, P., Girard, M., & Hartsfield, LA. (2013). Reasoning by inference: Further studies on exclusion in Grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 127, 272-281 doi: 10.1037/a0031641

Völter, C.J., & Call, J. (2017). Causal and inferential reasoning in animals. In: APA Handbook of 766 Comparative Psychology (Call, J., Burghardt, G., Pepperberg, I.M. & Zentall, T.R., eds.). American Psychological Association Press, Washington, DC, pp. 643-67

The experiment or story about Arthur, Griffin and Athena was fascinating. Could it be that female African Grey birds react differently to certain things than compared with the same species but a different gender. I’ve often wondered if the males react directly than the females; being that I’ve a female.

I have a female budgie named Dollar, have had her 63 weeks. In that time, I’ve repeatedly seen the result of Dollar having been watching what I do, particularly with my hands. One striking behavior that began after less than 3 months was that Dollar would go to the specially made “holder” I had made for her to work on Nutriberries, it gives her leverage and keeps the Nutriberry in one place. Dollar began going to the empty holder and pushing it toward me. I quickly realized she was asking me to go get a Nutriberry and put it in her holder! A year later, she still does this even when the holder is located outside her “play area.” She locates the holder, then pushes it toward me. 2. I taught Dollar early to leave her cage when she heard the sound of budgies playing on my computer which is on my desk in the living room. But once she got to the computer she would search frantically for the “other budgies.” Result: she began to go to my fingers and nibble on them and then would hop on my hand and pull hairs on the back of my hand. She would then stretch her whole body in the direction of the computer screen. She clearly wants to be lifted close to the screen! (Before this, she was always reluctant to step up on my hand or fingers.) A related behavior: Dollar (one her own!) began pulling the mouse cord around and then hoping on my hand and hair-pulling. She has made the connection between moving the mouse and making budgies appear on the computer screen. There is no doubt in my mind: this. bird weighs just 34 grams but is obviously sentient and capable of reasoning and logic.