Contents

In my previous column, I discussed how we unintentionally stimulate our birds sexually and then we are stuck with a number of unwanted behaviors. It is also important for bird owners to understand the female bird’s reproductive system. Here is a detailed account of exactly what goes on during the egg-laying process, which will be especially helpful for those who wish to raise birds.

In my previous column, I discussed how we unintentionally stimulate our birds sexually and then we are stuck with a number of unwanted behaviors. It is also important for bird owners to understand the female bird’s reproductive system. Here is a detailed account of exactly what goes on during the egg-laying process, which will be especially helpful for those who wish to raise birds.

A hen’s ovary develops to its functional state based on the life span of her particular species. Many of the larger psittacines have development at about 4 to 7 years of age, while in smaller parrot species it is at 1 to 3 years of age. All birds have ovarian development during the breeding season; the ovary then shrinks during the non-breeding season.

As the ovary grows and matures, there is an outer definable cortex where the follicles develop with an inner medulla. The medulla becomes an irregularly shaped vascular zone that is centrally located. The vascular zone has nerves and blood vessels that supply the ovary along with smooth muscle and interstitial supporting cells. The vessels to the ovary come off of the abdominal aorta and the vena cava as short stalks, making it very difficult to remove the ovary from birds without significant bleeding from these large blood vessels. When the ovary is stimulated hormonally in the lay period, it bulges into the coelom or abdomen.

The ovary is located just caudal (or distal) to the lung and slightly caudolateral to the adrenal gland. This landmark is used for endoscopy when sexing a bird to determine its gender, called surgical sexing (a blood test is another way to determine a bird’s gender).

Three Phases of Development

In birds with a seasonal laying period, there are approximately three phases of development of the reproductive system: a prenuptial acceleration phase, a culmination phase, and a refractory period. During the onset of lay, or the prenuptial acceleration phase, the follicles begin to develop into a hierarchical pattern so that they don’t reach maturity simultaneously. As egg laying commences during the culmination phase, the ovary resembles a bunch of grapes because of its follicular development. During the resting phase, or the refractory period, the ovary diminishes in size as each follicle is reduced significantly and the ovary becomes quiescent (inactive).

During the acceleration phase, the oviduct increases in size to reach its full development in the culmination phase. This second phase is when the oviduct is capable of turning the ovum into an egg! In the resting phase, the oviduct shrinks to a very small thread-like structure. While these structural changes are occurring, there are hormonal and behavioral changes that are happening as well. I discussed some of those in the last column.

Ovulation

Birds have a variety of mechanisms to reduce weight, which serve to compensate for part of the expenditure of energy for flight. One way to reduce weight is to only have the reproductive organs large during the culmination phase so that the bird does not have to carry all of that weight around other times of the year — particularly during migration! Another way for birds to carry around less weight is the laying of an egg that is incubated externally. Interestingly, no avian group is viviparous, that is, bears live young like people and other mammals. However, from their reptilian ancestry birds inherited an elaborate development process to form a heavily yolked, or cleidoic egg.

In order for the hen to have multiple offspring, each fertilized ovum must be fertilized sequentially and travel down the oviduct to form a shelled egg for external incubation. During the laying period or culmination phase, each follicle enlarges in a hierarchical arrangement so that they don’t mature simultaneously.

Each large follicle is suspended by a stalk that contains smooth muscle and a blood and nerve supply. The follicle is composed of a primary oocyte surrounded by six layers of tissue. The nerve supply consists of both adrengeric and cholinergic fibers, suggesting a role in ovulation. These tissues have an endocrine role, providing communication between the ovary and oviduct with the passage of each ovum to form an egg. Many birds have a stigma on all large follicles. This area is the point where the oocyte breaks through the follicular wall during ovulation.

Ovulation occurs under the influence of multiple factors, including a preceding LH spike (acute rise of luteinizing hormone). Ovulation, in the chicken, and presumably in other species, occurs at a relatively fixed time after oviposition or the time when the egg is laid (one-half hour in chickens). Ovulation with subsequent ovum capture by the infundibulum must involve at least some neural control.

Determinate Egg Layers

Some birds, such as crows and budgerigars (aka “parakeets”) are determinate layers. These birds lay a fixed number of eggs in their clutch. Indeterminate layers, such as cockatiels, are those bird species that can replace a lost egg by laying another. Double clutching is a technique to increase the number of eggs normally laid in a clutch by removing an egg, thereby stimulating the hen to replace that “lost” egg. This is why you should not remove the eggs in the nest of your companion bird as she lays them — it will cause her to continue laying eggs, much like chickens do!

Internal Laying

The infundibulum is the proximal opening of the oviduct. This capture is helped by the anatomic arrangement of the left abdominal air sac. This air sac surrounds the ovary in its ovarian pocket except caudally, thereby acting as a conduit for the ovulated ovum to “fall” into the opening of the infundibulum. However, not all ovulated ovum are captured successfully. When the ovum does not reach the oviduct, but is laid into the coelomic cavity, it is termed internal laying. This process occurs more frequently at the initiation and termination of the culmination phase. Interestingly, this ovum can be absorbed without problems by the hen or can lead to egg peritonitis (the presence of yolk material in the coelomic cavity).

A different process occurs with egg binding, when the egg gets “stuck” in the shell gland or uterus. This is common when birds do not get enough calcium or protein in their diets, but there are other reasons as well. Seed-only diets are deficient in calcium and the amino acids that form the building blocks of protein, which is why a nutritionally balanced diet is especially important.

Egg Fertilization

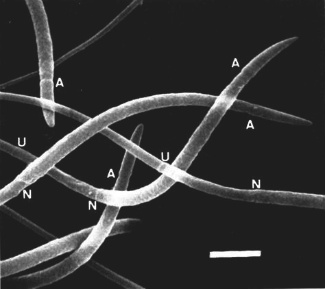

Once the ovum reaches the infundibulum, spermatozoa must penetrate it rather quickly before albumen is laid down. This requires a well-timed wave of sperm to be in the appropriate location at the time of ovulation. In chickens, there is only a 15-minute window of time for penetration of the sperm for fertilization to occur. Fertilization is presumed to occur in this very proximal portion of the infundibulum.

After ovulation, the follicle where the ovum was expelled from undergoes rapid regression and absorption. During this regression, the cells in this follicle are replaced with hypertrophied granulosa cells laden with lipid. This lipid is converted to progesterone and other sex hormones to prime the oviduct for the development of the egg and to make the hen nesty and broody, which compels her to sit on her eggs for the required incubation time.

When the correct number of eggs are laid, the hen becomes involved in the incubation and caring of the chicks. It is during this time that the remaining follicles stop developing, and the ovary begins to regress until the next breeding season. As discussed in my previous column, an unsuspecting owner might unintentionally stimulate their bird to go back into egg-laying production or at least keep them in the stage of reproduction right before the lay period.

How The Egg Is Formed

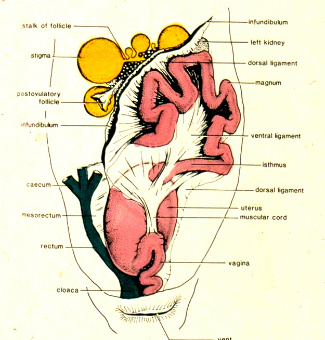

The left oviduct in most birds is responsible for the formation of the shelled egg. It consists of five basic components that are only distinguishable histologically or by the stage of development of the egg in that portion of the oviduct. These components include, from proximal (in relation to the ovary) to distal: infundibulum, magnum, isthmus, uterus or shell gland and vagina.

The wall of the oviduct is similar in its basic structure to other tubed organs of the body. It consists of an epithelium with an underlying submucosa, external layers of smooth muscle, and covered by peritoneum. The epithelium of the oviduct has two predominant cell types; a ciliated and a glandular cell that is similar to a goblet cell.

The number of each cell type varies in each portion of the oviduct based on its function. For example, the magnum has a much larger proportion of unicellular glands, involved in the production of albumen. The ciliated cells have cilia that beat toward the cloaca in most areas.

There are multicellular tubular glands that are found opening into mucosal folds in each region of the oviduct except for the vagina. The mucosal folds spiral slightly along the oviduct to help rotate the eggs as it moves distally. The outer layers of smooth muscle are thought to propel the developing egg down the oviduct and transport the sperm by reverse peristalsis to the infundibulum.

Infundibulum

The infundibulum consists of a funnel for ovum capture and a tubular region. The funnel opening is toward the ovarian pocket of the abdominal airsac. Sperm have been observed to be stored in the glandular grooves and tubular glands of the infundibulum. The release of the ovum causes the release of the sperm into the area for fertilization. It must be fertilized at this point before traveling to the next region.

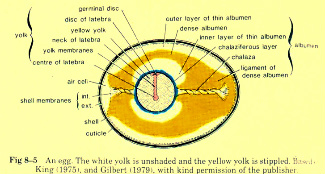

The tubular region is also described as the chalaziferous zone. The tubular portion secretes a thin layer of dense albumen, the chaliziferous layer of albumen. These chalazae twist around the yolk, and thereby tighten as they turn when traveling down the oviduct. In chickens, the ovum passes through the infundibulum in approximately 15 minutes.

Magnum

The next region of the oviduct is the magnum, the site where the majority of the albumen is added to the egg. The albumen is secreted primarily by the numerous branched tubular glands. The ovum remains in the magnum approximately three hours in chickens.

Isthmus

The isthmus is the site for the formation of the two shell membranes (inner and outer), the addition of a small amount of protein to the albumen and the initiation of calcification of the shell. Only the glands of the isthmus produce sulfur-containing amino acids, important for shell membrane production. Passage through this short segment of the oviduct takes approximately 75 minutes in chickens.

Uterus or Shell Gland

There are two anatomically distinct portions of the uterus or shell gland in fowl. The cranial part is short. The distal portion is pouchlike and where the egg remains for approximately 20 hours in fowl. In addition to longitudinal folds, there are transverse folds that result in lamellae with a leaf-like appearance. These lamellae flatten against the developing shell. The uterus initially is responsible for plumping of the egg, whereby water and electrolytes are added to the albumen. This occurs first and then calcification proceeds.

The uterus has a remarkable ability to extract large amounts of calcium from the blood stream, thereby requiring the release of calcium stored in the long bones. The shell consists of shell membranes, testa and cuticle. The testa is composed of an organic matrix with calcite — a crystalline form of calcium carbonate. The outermost organic layer is the cuticle. The cuticle is water repellent, reduces evaporative loss, and it forms a barrier for microorganisms.

The vagina is a conduit for the egg to pass from the oviduct through the cloaca and out the vent. The process of expelling the egg is termed oviposition. The time required for oviposition varies among species. The vaginal sphincter separates the uterus and vagina. This sphincter relaxes at the onset of oviposition. It is the smooth muscles of the uterus that propel the egg through the vaginal sphincter and into the vagina. The presence of the egg produces neuronal stimulation. This causes a bearing down reflex of the cloaca, passing the egg out through the vent.

Additionally, there are folds in the region of the sphincter, the spermatic fossulae or the sperm host glands. These glands represent the primary site for sperm storage, an important adaptation to allow for rapid fertilization of the next ovum immediately after its ovulation. Ovulation often occurs shortly after oviposition of the egg that is fully formed.

The Egg Inside & Out

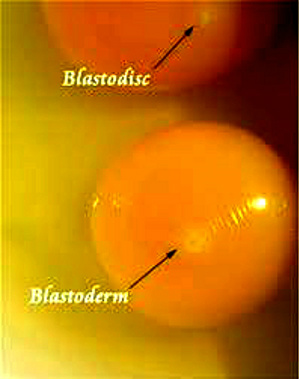

The fully formed egg is composed of a germinal disc, yolk, yolk membranes, albumen, and a shell. The germinal disc is normally a circular, opaque, whitish spot. In chickens, it is approximately 3 to 4 millimeters in diameter. It represents the remnant of the nucleus. If the ovum is fertilized, it is termed the blastoderm and represents the cells of the developing chick embryo.

The fully formed egg is composed of a germinal disc, yolk, yolk membranes, albumen, and a shell. The germinal disc is normally a circular, opaque, whitish spot. In chickens, it is approximately 3 to 4 millimeters in diameter. It represents the remnant of the nucleus. If the ovum is fertilized, it is termed the blastoderm and represents the cells of the developing chick embryo.

The yolk consists of mostly lipo- and phosphoproteins. The yolk serves as the main source of nutrition for the developing embryo. There are four yolk membranes; two from the follicle and two provided by the infundibulum. These membranes from a barrier between the yolk and the albumen, but allow for the movement of electrolytes and water.

The albumen is less viscous than the yolk. Its solid component consists of ovomucin, which is mostly protein. The albumen in an egg is divided into dense and thin albumen. The dense albumen has a higher content of ovomucin than the thin albumen. The chalaziferous layer surrounding the yolk membranes is dense albumen. The chalaza represent twisted strands of ovomucin fibers. The egg has an inner and outer layer of thin albumen with a middle layer of dense albumen. The albumen suspends the embryo in a relatively aqueous environment. Its protein component acts as a source of nutrition for the embryo. Albumen also is considered to have antibacterial properties.

The shell, as indicated above, consists of the two shell membranes, the testa, and the cuticle. Generally, the size of the egg is related to the size of the parent. However, its relative weight diminishes as the body weight increases. The eggs of precocial species (offspring are born covered with down, having open eyes and capable of leaving the nest within a few days of hatching) are often larger than those layed by altricial species (helpless, naked and blind when hatched. The shape is also species-dependent and appears to be related to the shape of the hen’s bony pelvis. Spherical eggs are associated with a deep pelvis oriented in the dorsoventral direction, while elongated eggs occur with dorsoventral narrowing.

The owner should examine the eggs and note the sequence of eggs when they are laid. When the shell thins or the eggs become misshapen, there is great cause for concern. This represents a hen that is not able to provide enough calcium and/or protein in the diet. There may be additional concerns, so it is important to get the bird to an avian veterinarian as soon as possible.

Coloration of the egg shell is very diverse. These ranges of color result largely from variations of two pigments; the red-brown porphyrins and the blue-green biliverdins. These pigments are deposited as crystals throughout the calcified testa. The surface texture of the shell also varies. Most commonly, the shell is smooth with a slight sheen. It can also range from the highly glossy egg of woodpeckers to the pitted eggs of the ostrich.

Birds are remarkable, and egg laying is a unique biologic event. It was designed to reduce weight with flight. We often use the egg as a symbol of birth and hope. With spring come eggs and hope for a new year!

We hav a 22yr oldSulphur crested Cookatoo. We rehomed her with us at age 11 and know nothingabout her perevious life. She started laying unfertilised eggs around the 2nd year after we had her. Her first egg was splattered from her perch. 2 months later she laid an egg on the feet of her Human Partner (my husband) The next hatching came about 3 months later which she laid on the carpet under our computerThis time she laid 2 eggs 2 days apart. She was very protective of them and sat on them and rolled them. After 5 weeks when she could feel no movement she ignored them. we had about 2 years before she laid another egg on th floorof the bathroom(thisis her favourite room) we had put straw ,newspapers in a cardboard box tht fit her but she prefered the floor. This time she lost interest soon afterwards

Is this normaland is she losing too much calcium