Understanding the cloaca and cloacal prolapse

The cloaca is a common receiving chamber for the reproductive, urinary and gastrointestinal systems. Each system empties into its own ‘compartment’, which is separated by folds. The vent is a transverse opening in the body wall through which droppings and reproductive products are expelled from the cloaca.

Prolapses can originate from the cloaca, oviduct or intestinal tract. The cloaca normally prolapses during egg laying or oviposition, and normal retraction of the cloaca may be slowed or absent in an obese hen or one with hypocalcemia. Excessive abdominal contractions caused by an abnormal egg, dystocia, cloacal disease, gastrointestinal disease or chronic mastubatory behavior can also promote prolapse (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Cloacal prolapse in a parakeet. Photo credit: Dr. Isabelle Langlois. Click image to enlarge.

Key points of urgent care

Cloacal prolapse is a serious and potentially life-threatening problem. When prolapse is identified during physical examination, liberally and gently apply water-soluble lubricant to keep all exposed tissues as moist as possible.

The prolapse should be reduced as soon as possible to prevent further trauma, infection, and necrosis of cloacal tissue.

- Induce general anesthesia.

- Place the patient in dorsal recumbency.

- Hypertonic saline, 50% dextrose or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) may alleviate some of the edema in prolapsed tissues making reduction easier.

- If an egg is within the prolapsed tissue, perform ovocentesis. Insert an 18-gauge needle to aspirate egg contents, then apply pressure laterally to collapse the eggshell.

- Gently swab the tissue for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing.

- Gently clean exposed tissues by lavage with sterile saline and dilute antiseptic solution.

- Replace prolapsed tissues using an appropriately sized, lubricated, blunt probe or gloved finger.Do not merely stuff tissues back into the cloaca. Tissues should invert back inside in an anatomically correct orientation, like a sock being turned inside out.

- Place two (or three) simple interrupted or horizontal mattress sutures across the vent using 3-0 to 5-0 non-absorbable monofilament suture such as nylon or PDS on a fine-curve cutting edge needle.

Make small, shallow parallel bites. Purse string sutures are not recommended for birds due to anecdotal reports of cloacal atony. Pull both ends of suture material with equal tension and take care not to cinch sutures down tight to minimize the risk of post-operative swelling.

Leave a lubricated cotton-tipped applicator or red rubber catheter in place while placing sutures to ensure the opening is large enough for droppings to pass.

Case management

Stay sutures provide a temporary treatment and should be left in place at least 48 hours. Meanwhile the underlying cause of the prolapse must be identified and addressed.

Signalment

Reproductive disease is most commonly seen in small parrots:

- Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus)

- Lovebird (Agapornis spp.)

- Budgerigar parakeet (Melopsittacus undulatus)

History and examination

Obtain a complete history including information about mineral supplementation. Carefully evaluate droppings. Blood may be seen in the droppings with dystocia.

In addition to standard questions about husbandry and clinical disease, the reproductive history should include:

- When was the last clutch (or collection of eggs) laid?

- How many eggs were laid?

- Were the eggs normal in size and shape?

- Has broody (or reproductive) behavior been observed such as a increase in appetite, particularly for calcium-rich foods? Does the bird seek dark places or exhibit nest-building behavior like paper shredding? Some hens may become cage protective or aggressive?

A chronic egg layer produces a larger than normal clutch or it produces repeated clutches, regardless of the existence of a suitable mate or the season. Without special modifications to the diet, repeated egg production leads to a depletion of body calcium and protein stores, which may promote egg binding, dystocia, and weight loss.

Diagnosis of prolapse is based on physical examination findings. Exam reveals prolapsed tissue through the vent that may be intermittent or persistent. There may also be hematochezia, and if the cloaca is infected, there may be foul-smelling droppings.

With a uterine prolapse, the lumen of the oviduct gives the tissues a “donut-like appearance”. Although prolapsed tissue can become edematous, the longitudinal folds of the uterus are still easily visible in most cases. With a rectal prolapse, the colon appears as a tubular structure devoid of folds.

Complete examination of the bird with cloacal prolapse should include careful evaluation of the oropharynx and crop, coelomic palpation, and inspection of the vent.

| Oropharynx |

|

| Crop |

|

| Coelomic palpation |

|

| Vent |

|

Diagnostics

After the prolapse has been reduced, work to identify the underlying cause of dystocia. Obtain a minimum database whenever possible including a complete blood count, biochemistry panel and survey whole body radiographs.

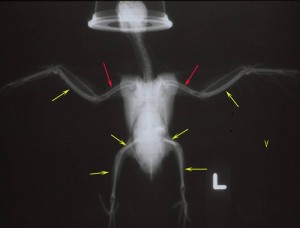

Look for the presence of osteomyelosclerosis on radiographs. Ossification of long bones or osteomyelosclerosis is a normal radiographic finding in the hen gearing up to lay eggs is. Bone marrow ossification occurs secondary to rising estrogen levels and provides a critical calcium reserve for the hen to shell and pass the egg through the reproductive tract (Fig 2). The absence of osteomyelosclerosis in a hen with a shelled egg is very significant because this suggests she lacks the calcium reserves needed for normal uterine contraction waves that will expel the egg.

Figure 2. Ossification of long bones or osteomyelosclerosis (yellow arrows) compared to normal radiographic appearance of bone in the bird (red arrows). Click image to enlarge.

Therapy

After the prolapse has been reduced, place the patient on systemic antibiotics, anti-inflammatories (Meloxicam 0.2-0.5 mg/kg PO, IM, SC q12-24h), and possibly a stool softener such as lactulose (200 mg/kg PO q8-12h).

If egg laying played a role in the prolapse, also administer a drug to inhibit egg laying such as human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (500 IU/kg IM on Day 1, 3 and 7), or more commonly, leuprolide acetate (Depo Lupron, TAP Pharmaceuticals) (100-200 µg/kg IM q 2-4 weeks). Additionally improve the bird’s plane of nutrition, particularly the calcium and protein content of the diet. Also recommend behavioral and environmental changes that can halt egg laying. See the Client Handout: Chronic Egg Laying.

Once all medical and behavioral issues have been corrected, if the prolapse persists or recurs, then an advanced surgical procedure can be considered such as ventplasty or cloacopexy. Salpingohysterectomy may also be recommended to prevent future episodes of egg retention or in cases of oviductal prolapse.

References

References

Bowles HL. Evaluating and treating the reproductive system. In: GJ Harrison, TL Lightfoot (eds). Clinical Avian Medicine. Palm Beach, FL: Spix Publishing; 2006. Pp. 519-540.

Rosskopf WJ, Woerpel RW. Avian obstetric medicine. Birchard SJ, Sherding RG (eds). Saunder’s Manual of Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 2000. Pp. 1451-1458.

Speer B. Diseases of the urogenital system. In: Altman RB, Clubb SL, Dorrestein GM, Quesenberry K. Avian Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997. Pp. 633-644.

Pollock C. Presenting problem: Cloacal prolapse in birds. April 25, 2012. LafeberVet Web site. Available at https://lafeber.com/vet/presenting-problem-cloacal-prolapse-in-birds/